Explaining Net Present Value and the Time Value of Money

According to many in the media, Larry Scott has had a rough year or so. On the field, for the second year, his conference was shut out of the College Football Playoffs, and the Pac-12 has had a similarly dismal performance in the NCAA Men’s Basketball tournament. Off the field, there have been problems from questionable officiating to questionable salaries to questionable leasing decisions.

Those controversies are dwarfed by a much larger one: does the Pac-12 have a questionable business model?

The question hinges, it seems, on a key strategic point: The Pac-12 in 2012 prioritized owning 100% of the conference’s media rights. The defenders of Larry Scott—including himself, AJ Maestas, Joe Ravitch and even other athletic directors—summarize the defense along the lines of what Tom Stultz told AthleticDirectorU a while back:

“The true value of the conference’s strategy won’t be fully known until the next round of rights negotiations. The Pac-12 will have more options available to it than any other conference because of the rights it has retained. Whether or not that pays off will be clear once those negotiations occur.”

I’ve been frustrated by this debate, though, because I haven’t seen any good numbers on it. Do we really have to wait until 2025 to judge this strategy? The defenders of the Pac-12 hardly ever quantify the strategic decisions above. I have a saying on my website, one of my core beliefs, that, “Strategy is Numbers”. If you don’t run the numbers, you don’t actually have a strategy.

(I happen to be a diehard UCLA fan, so the success or failure of the Pac-12 is also pretty important to me. I was one of the few people watching UCLA gymnastics and volleyball on the Pac-12 Networks, until AT&T U-verse dropped them.)

As the Pac-12 considers selling 10% of its media rights to a strategic partner, it seems like some numbers can help us understand if Larry Scott and company made the right decision in 2012, if they’re making the right decision now, and what they should do in 2025. Since Larry Scott doesn’t share detailed numbers with his own Athletic Directors, it seems all the more relevant that someone should sketch out the stakes.

Since this is AthleticDirectorU, I’m going to lay out my process so that hopefully other ADs and leaders in college athletics could learn from my approach. Moreover, I’ll teach a few points about business strategy, that apply as much to college sports as consumer packaged goods. As for the numbers, I’m relying on the fantastic reporting of a few people, including Jon Wilner at San Jose Mercury News, John Canzano at The Oregonian and others.

To be clear, I can’t actually answer the question definitively. I don’t have access to the financials of the Pac 12 beyond the broad strokes in the Form 990s filed to the IRS—and released 10 months late—so I have to make a lot of assumptions. But I can sketch out the terms of the debate in hopefully a more concrete way. This article will have two parts. Part I will explain some terms, and Part II will explain my estimates with final conclusions.

What You Can Learn From This

Time Value of Money

One of the keys for really judging the value of a decision is understanding the simple principle that a dollar is worth more today than in the future. My biggest complaint about most business reporting is that it ignores this rule. While journalists avoid it because it is hard to explain simply—an extremely famous political figure actually criticized it last fall—business executives are equally to blame (and often look more successful by ignoring it).

Net Present Value

Once you understand the time value of money, you should understand the greatest of all financial rules: The goal of a firm is to maximize the “net present value” of all their investments. This is a chapter—or multiple chapters—in any financial text book, so I can’t explain it all in one article. But hopefully you come away with the idea that whenever you hear a strategy—especially with a big up-front investment—you think, “Oh, how much do we need to make to justify that?” So let’s start there.

Problem: The Core Equation

In the case of the Pac-12, in 2012, Larry Scott and the Pac-12 made a bet on themselves. The bet, the key decision, was that he would launch the Pac-12 TV network. At the time, before the launch of the SEC Network, this wasn’t a no brainer decision. The Big Ten Network was doing well, but the Mountain West Network had folded. But the decision we’re judging today was made right after that: to launch without a strategic partner.

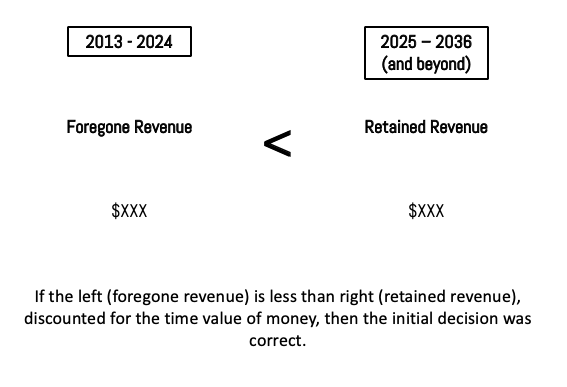

The reasoning was that a strategic partner would demand ownership in the network, which wouldn’t be worth it in the long run. In statistics, I always find it helpful to draw a picture. Since we’re all visual learners—learning styles haven’t withstood the test of time in the academic literature—I’m going to draw one here. Here’s that bet in the simplest picture form:

This investment seems to concede the point that if the Pac-12 Networks had signed on with ESPN or Fox Sports (or even an NBC Sports, an outside the box partner), that their reach and hence value, would be increased. As it is, the Pac-12 Networks never signed a deal with DirecTV, and worse, has since been dropped from AT&T U-verse. Subscriber fees may have even dropped over time too. As a result, the Pac-12 lags behind its peer conferences in annual distributions to member schools.

But the network defenders insist those losses are temporary. At the end of 2024, the Pac-12 will have all their media rights, Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 rights, every game for every sport. The value of those rights will make up for any of the losses, or so the argument goes.

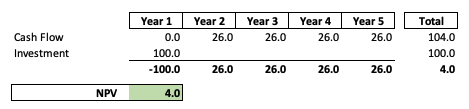

While it doesn’t seem like it, the foregone Pac-12 revenue is the equivalent of a “capital expenditure”. Or an upfront investment to get a future return. The best way to judge investments in your business is to use “net present value” (NPV). That is, you subtract how much you spent, and add up all your future cash flow. Then if the money made is greater than the money spent, you had a positive return, or positive NPV, and you make that investment. Take this hypothetical business plan:

This makes it clear that if you invest $100 million to earn $104 million, you made money. You take that bet. The bet Larry Scott made is like the above capital expenditure, it’s just spread out over 12 years. Usually, a company makes a big one-time investment—build a new plant, expand into Europe, launch a new product, buy a company—that takes place over a year or so. Larry Scott invested this money into the Pac-12 Networks over a 12-year period. It’s a longer time horizon, but the same principle. Moreover, even if the “investment” is foregone revenue, that is still real cash that would have gone to the conferences.

So the next step is to tally up how much the Pac-12 invested by not taking on a strategic partner. Once we know that, we can see the scale of the problem in front of Larry Scott and the Pac-12.

The Back of the Envelope Math

My goal with back of the envelope math is to find a few “key drivers” of revenue to get a sense of the problem. You know, so it can fit on the literal back of an envelope. Often, I pair this with “rules of thumb” which are common numbers or multiples that help explain an industry.

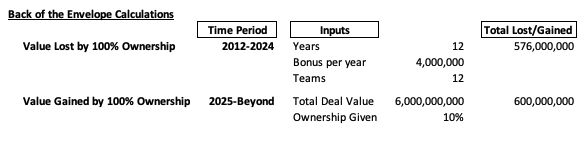

In this case, the first part of the equation could go like this: The Pac-12 hoped to earn about $5 to $6 million per school in Pac-12 Network revenue. It definitely isn’t—I’ll get to that—and the shortfall is something like $4 million per school. So assume they lost about four million per year per school.

Now let’s go to the 2025 and beyond period. Say the Pac-12 doubles the value of their media rights over the 12 years. That means $6 billion dollars. And since they’re looking to sell 10% of the conference’s media rights, let’s use that as a stand in for the rough percentage a partner would have owned going forward. In that case, the retained value of 100% of rights is $600 million.

Since $600 million is greater than $576 million, if the Pac-12 can generate $6 billion in media rights from 2025 and beyond, retaining 100% of all media rights was the right decision.

Oh, except for that pesky fact that a dollar in 2012 was worth more than a dollar in 2025 will be.

The Time Value of Money, Explained!

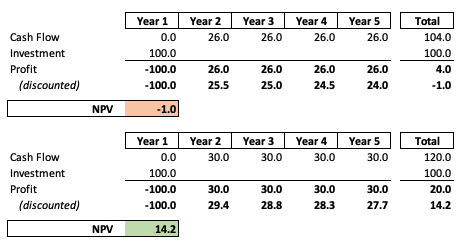

If Finance 101 has a rule—or even Economics 101—it’s that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. The key is figuring how much that is. (On my website, I explained it using Disney’s Lucasfilm acquisition.) Let’s start with that NPV table I used above. The future values are worth less than the initial value, so I need to discount all the values back to the “starting point”. Here’s how the initial table looks, and a version where the investment yielded $30 million per year, to show how the time value of money can start to impact returns at a 2% interest rate:

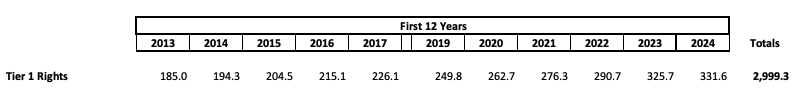

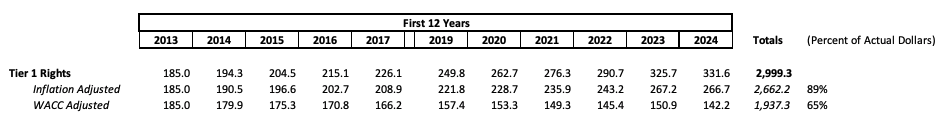

See the first investment actually lost money if you account for inflation. Let’s play that discounting game with Pac-12 media rights. In 2012, the Pac-12 signed a $3 billion dollar deal with Fox and ESPN for their Tier 1 media rights, meaning the most valuable games in football and basketball, for a 12 year period. That deal escalated over time by about 5%. (And these numbers again come from the incomparable Jon Wilner. I also had to add some more money at the end because it didn’t quite get to $3 billion.)

Like I said a dollar is worth more today, so now we “discount” those future values. And this is part of the art of finance. I’m going to show two different discount rates. First, the inflation rate. This is just the easiest to understand. I use 2%, even though recently we’ve been under that threshold, but it’s a nice round number.

The harder part is determining the “cost of capital.” Basically, the reason you discount is to account for the amount of risk in an investment. Think of this like the difference between high yield bonds and US treasuries. One is very risk so you get more interest and the other is very stable, so less interest.

There’s lots of complicated ways to calculate the cost of capital, but I make it easy and use this page from the NYU Stern business school. Unfortunately, sports isn’t included, but entertainment is. Entertainment investments should return a 9.4% return currently. If instead of launching a media network, the Pac-12 had taken their earnings each year and invested in a mutual fund of entertainment stocks, it should generate 9.4%. In my series on Disney, I used an 8% cost of capital, because it was lower last year when I started. I’m going to use that number today too (and this is conservative, so helpful to the Pac-12).

Here is that same table from above, with the values discounted, to show the impact of both rates:

So even a deal with an overall value of $3 billion dollars is worth less over 12 years than it seems on paper. And over time this really starts to bite into profits. If the Pac-12 is missing out on potential revenue for 12 years, it will need to make much, much more to account for the cost of capital in 2025. If you don’t account for that fact, well you’re just not spending your money wisely. (Well, not spending the public’s money wisely.)

Now that we know we should build an NPV model, and discount for the time value of money (and risk), we can re-ask our question: was the decision to launch a network without a strategic partner the right one in 2012?

(I’ll answer this question in Part II of this series early next week)

(The Entertainment Strategy Guy writes under this pseudonym at his eponymous website. A former exec at a streaming company, he prefers writing to sending emails/attending meetings, so he launched his own website. He’s also a product of the Pac-12 system, twice. You can follow him on Twitter or Linked-In for regular thoughts and analysis on the business, strategy and economics of the media and entertainment industry.)